I’ve been a huge Douglas Rushkoff fan ever since he predicted the future of viral media in his influential 1995 book Media Virus: Hidden Agendas in Popular Culture.

I was just a teenager then, trying to figure out whether I was Gen X, Gen Y, or whether it even mattered. As I grew up reading his books, Rushkoff was one of the few voices telling me not only did we matter, but we were going to change the world.

I just finished reading his latest book, Present Shock: When Everything Happens Now. Rushkoff is no longer talking as much about the future. This is probably because, as his book explains, the future is disappearing. In a society of always-on, interconnected devices, a market of infinite choice, and an economy that commodifies attention, regard for the future is being replaced by an obsession with the present.

Present Shock’s five beefy but breezy chapters are easy to summarize. Rushkoff makes his case by illustrating the collapse of the traditional narrative, the temporal schizophrenia of digital omnipresence, the “short forever” of today’s compressed timescales and the need to differentiate patterns to make sense of information. The book closes with a short chapter on America’s cultural obsession with zombies and the apocalypse (close to my heart as the leader of an apocalyptic rock band).

Rushkoff doesn’t so much change the way you see things as help you make sense of an increasingly interconnected world of complex relationships and “big data.” It’s an illuminating, lively read, if you have the attention to spare, of course. It’s not just a book that will hone your perception of the impact modern media and technology are having on our culture and society — it also serves as reminder of the value in occasionally escaping this Present Shock to enter long moments of focus and concentration. In the “meta” sense, reading this book is a perfect example of such a fruitful escape.

OK, that’s the Amazon review — so what does Present Shock have to say about how music is changing?

I could offer a lengthy narrative of my own, but I know you don’t have the time or attention for that. So allow me to comment on a few quotes from the book — those that resonated with my own experience analyzing music media and technology trends, a practice which continues to be inspired by Rushkoff’s books:

“The word ‘entertainment’ literally means ‘to hold within,’ or to keep someone in a certain frame of mind. And at least until recently, entertainment did just this, and traditional media viewers could be depended on to sit through their programming and then accept their acne cream.”

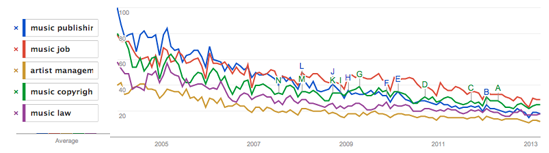

Corporations are losing control over the market for and culture of music. Their apparatus of control for the past century has been technology and law. But now technology is evolving too fast for law to catch up. Culture is on the leading edge of this evolution. The market is struggling to remain relevant. Professional musicianship is on the decline. Through all of this change, a big picture is emerging: music is not just for entertainment (and through correlation, for profit). This is a huge realization that has yet to dawn on the defenders of the “old” music business. But it’s second nature to digital natives. The commodification of music depends on its being perceived primarily as an entertainment product. But music’s true purpose is to bond us socially in shared experience. Context is the new commodity. Attention/time is the new scarcity. Entertainment products are no longer enough. We want to make our own experience. We don’t want to be ‘held within’ someone else’s meaning. We want to create our own meaning — the semiotic democracy in action.

“The Occupy ethos concerns replacing the zero-sum, closed-ended game of financial competition with a more sustainable, open-ended game of abundance and mutual aid… It is not a game that someone wins, but rather a form of play that — like a massive multiplayer online game — is successful the more people get to play, and the longer the game is kept going.”

I’m a huge champion of the “amateurization” of music. All signs point to a world with a greater quantity of music, being played and listened to with greater frequency, with a greater diversity of styles. We may be losing a certain subjective “quality” of music as defined by big studio budgets, virtuoso performances and mass appeal. We may be losing a “depth” of listening as defined by repeat listens, compositional literacy, and attentiveness to the nuances of performance and recording. Change is going to be both bad and good, but when contrasted with the “zero-sum” game of the “old” music industry, I see a clear net benefit to our culture and market where “more people get to play.”

“When everything is rendered instantly accessible via Google and iTunes, the entirety of culture becomes a single layer deep.”

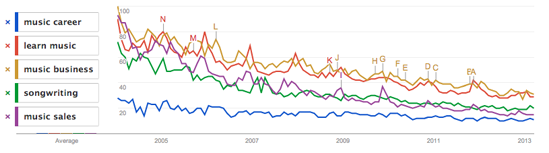

One of the biggest tensions in IP law is between third-world cultures whose ancient traditions have fallen into the public domain, and the first-world exploiters who appropriate this collective creativity from indigenous societies for profit. Both sides too often miss the point: So-called “traditional knowledge” must and will be free to appropriate for future creativity to flourish. Conversely, the profit in appropriating the work of others is rapidly shrinking as we culturally assimilate a truth we too often deny in our Western Romantic concept of authorship: the creative act is based on appropriation. This is second nature to the creators of remixes and mashups — the idea may never resonate with older generations. But believe me, when culture is “a single layer deep,” we enjoy the ultimate creative freedom, swimming in the sum total of humanity’s creativity. All existing meaning at any time can be appropriated, remixed or transformed to create new meaning. We still have to watch out for the dangers of hegemonic, corporate monoculture on the one hand, and lazy, uninspired copycat music on the other. But “Present Shock” means our attention is too fleeting to be “held within” either the traditional cultures we grew up with, or the co-opted, for-profit cultures sold to us. The cultural playing field may not be equal, but it certainly has been “leveled” by technology.

“The great peer-to-peer conversation of the medieval bazaar, which was effectively shut down by the rise of corporate communications, is back.”

The ‘cathedral’ represents a top-down, hierarchical approach while the ‘bazaar’ is a bottom-up, open-source approach. Jacques Attali’s brilliant, essential, but painfully dense Noise: The Political Economy of Music is perhaps the best exploration of the relationship between the cathedral and bazaar in the context of music. It also happens to be a central theme in the book I’m writing: what is the nature of the relationship between the ‘top-down’ architects of our musical culture/market, and the ‘bottom-up’ flow of musicianship and musical creativity/productivity?

By invoking the bazaar, Rushkoff’s sentence here immediately reminded me of The Cathedral and the Bazaar, a foundational open source essay by Eric S. Raymond, published in 1999. While his essay was mostly about software engineering, he proved a core thesis that “given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow” — in other words, the collective authorship power that digital technology provided was, at least in software engineering, a vast improvement over sole authorship of the kind encouraged by the IP industry since the inception of copyright. I believe the same to be true of music.

Of course, the cathedral started out not as a metaphor but literally as church control over the culture, market and technology of music. Over time, this gave way to corporate control over music, which retains a firm but tenuous grip on our auditory culture and market to this day. Rushkoff’s acknowledgement that we are returning to the ways of the bazaar should be wind in the sails for anyone who loves music and prefers a productive culture over a profitable one.

All one need to do is listen to a few mash-ups to hear the sound of the bazaar approaching loud and fast.