David Byrne thinks musicians are doomed by streaming music.

More music is being made and listened to with greater frequency, diversity and depth than ever before in human history.

But musicians are doomed.

Here are my issues with Byrne’s flimsy refutations of “counter-arguments” to building a business around free access to music:

“1. Recorded music -— and especially the idea of making money from it —- is so 20th century. Suck it up and move on.”

If not by selling access to recorded music, Byrne asks, “what is the alternative model for making a living” for musicians?

First, there’s the assumption that all musicians make money from recordings. Let’s acknowledge the many composers and performers who aren’t recording artists that are already making livings without exploiting their sound recording copyright.

Second, let’s also acknowledge that musicians never have earned 100% of their living from recordings. The bulk? Sure. Performance is an important and fast-growing part of the industry. Bands can and do produce and release successful albums in totality without any “team” helping them.

Third, there’s a complete lack of understanding as to how value is created around free access to music these days. For being such a musical visionary, Byrne doesn’t seem to realize that a new music business is dawning where fans directly patronize artists and fund their works. This is the era of the niche artist supported directly by the fan, the rejection of the hit song economy. It’s time to question corporate-hijacked copyright and government-decreed royalty entitlements as the basis of musician income.

Nobody thinks crowdfunding will “replace” royalties, that’s not the point. The point is that government-decreed, corporate-lobbied copyright exploitation rates are anachronistic in the digital age. We need new models. Byre, Lowery and the pro-copyright pro musician (but not necessarily pro-musician) cabal perpetuate the myth that music career failures are due to external forces (“piracy”) and not their own failure to adapt.

Alarm over the idea that value is shifting from the song to the fan is understood but unwarranted. Think beyond the numbers you see getting smaller on your royalty check. Right now, at this very moment, musicians are thriving. Byrne is the minority. We laugh at complaints about your royalty check, the epitome of a first-world problem. Most musicians never see a royalty check. Not because their music lacks quality or an audience, but because they don’t understand the music business, and the whole thing is set up to exploit them. Literally — copyright exploitation is how the old model derives value.

Thankfully, that will soon be behind us. The new model (well, really the “original” model of music before intellectual property law existed) derives value from the direct relationship between artist and fan. Technology brings us back to that model by allowing for songs to be produced, marketed and shared at costs that continue to diminish. We are all connecting, and the copyright regime is more of an obstacle than a boon to musical creativity and productivity.

Yet despite three labels owning ~70% of the rights to the world’s music (thereby largely dictating the terms that streaming companies do business), musicians aren’t just surviving, we’re thriving. More recordings are being made than ever before.

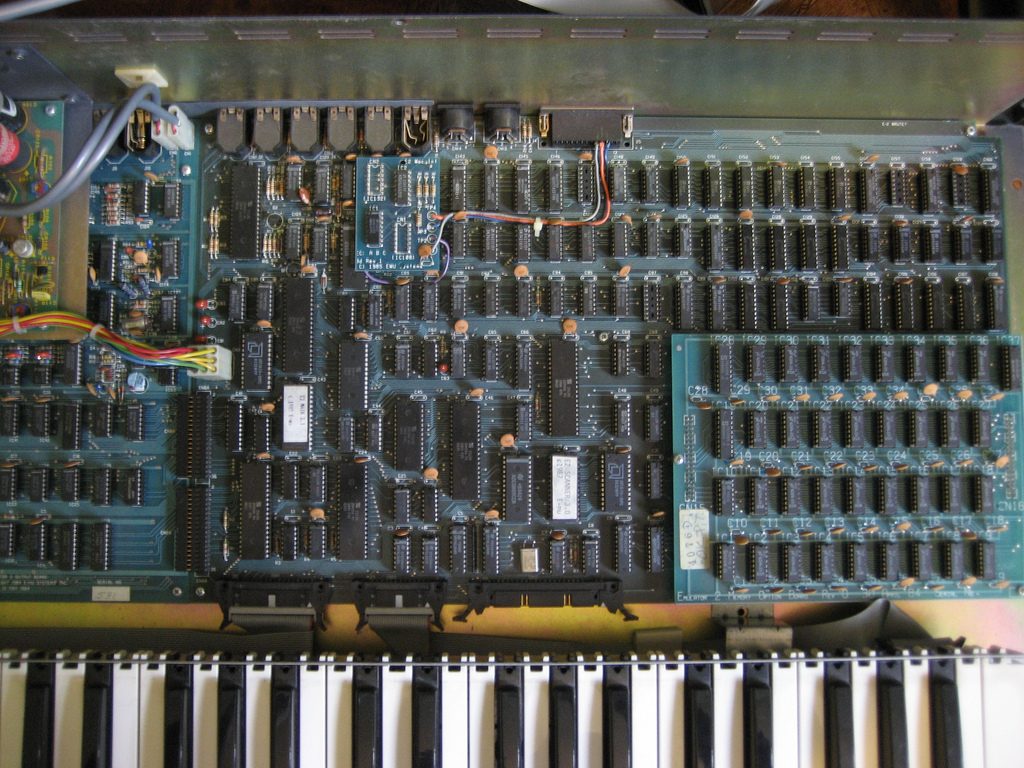

Again, for such a tech-conscious person, how can Byrne miss the recording studios in every musicians’ basement? How can he miss broadband and mobile? A world of ubiquitous, free flowing music. Each song an opportunity to be heard, and an opportunity to be paid.

Recorded music still has great value. Free or near-free access is not a genie that’s going back in the bottle, nor should it. Free access to music is best for most musicians and all fans. Some pros will get smaller paychecks — particularly those who relied on government-decreed royalty entitlements and lawyer/manager fees for squeezing blood from the stone-cold labels. That paradigm is shifting in a more ethical direction, and we should be championing it by adapting, not wringing our hands in paranoid nostalgia.

“2. The move to streaming services as the principal means of music consumption inevitably does some damage. That’s how the world works and how things progress. Progress is disruptive. One simply has to adapt to the inevitable.”

Well, yeah. Duh. Nothing is ever black and white. There are going to be benefits and drawbacks with any major change like this. Progress is both disruptive and inevitable. We have to look at whether digital music is a net positive or negative, and I continue to be stumped by folks who think music or musicians are at risk in a world of abundant creative production. The only thing being devalued is gatekeeping access to music, and there are numerous other revenue streams that musicians today are tapping into to power their careers.

Byrne makes it sound like all of the sudden, every musician doesn’t know how they’re going to make a living. All he has to do is take a look at the musicians succeeding by straddling the old model and the new, rather than fighting the future, which by definition, is inevitable.

Byrne goes so far as to categorize a group of people as “digital and technological inevitablists”, which won’t pass a spell check.

Some deaths are inevitable: The rotary phone… the fax machine… recorded music “ownership”. I mean, we’re not still using sharpened rocks to cut our meat?

So, obviously, Byrne says, “the content will run out eventually” if sound recording copyright loses its value.

Say what now? More music is being made and heard than ever before. On the whole, most musicians are taking advantage of the changes in the music business. There is a small but vocal minority of Byrnes and Ribots simply aren’t connecting directly with their fans and offering the kind of value that would render these worries of selling access obsolete.

Musicians are not under threat just because the musicians who can’t figure out how to switch from copyright exploitation to something else are blogging a lot about it.

Thousands of established artists have already embraced crowdfunding and taken control of their careers. They stopped wringing their hands and got them dirty taking control of their own careers.

“3. Scale will make the difference. Your concerns and fears are premature because if these services are allowed and encouraged to grow and reach their ultimate potential- they will be 20 times larger than what they are now in North America —- then artists will indeed make a decent living from this music consumption model.”

I don’t think anyone believes musicians will make a living solely from streaming music, or that streaming music will dollar-for-dollar replace CD sales or downloading.

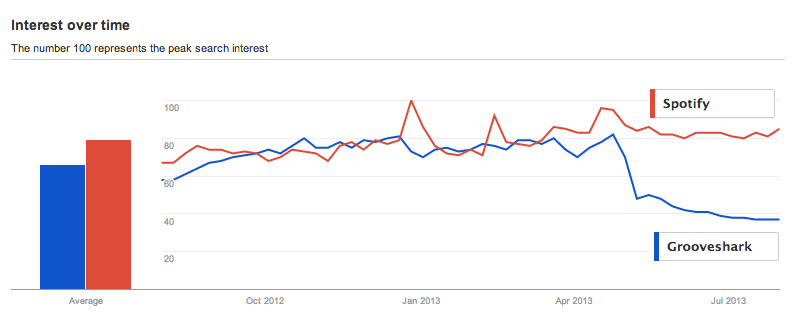

I also think any reasonable person sees streaming music having endemic financial problems, even as it scales to enormous user bases. The record labels are just squeezing too much juice out of the system for tech companies to make a decent profit.

Byrne obviously doesn’t realize what he’s saying here: “Monopoly, however, has not historically been good for consumers or for innovation -— regardless what tech companies say. Power corrupts; it’s a given.”

So… uh… this is awkward, but, you know copyright IS a monopoly, right? The very right you’re defending has historically not been good for consumers or for innovation. So, yeah, thanks for making my point for me.

Byrne ends on a note that we need more transparency, which most people in the tech world agree with and are striving to provide. Meanwhile, ASCAP and BMI have magical secret licensing calculations and the labels hide from their artists everything they’re not legally pressured to show.

“4. The Internet has been good for artists’ independence. They are freer now than ever before -— they can record more cheaply and even control their distribution, if they want to.”

OK, so Byrne knows about the democratization of recording, distribution, marketing, sales, merchandise, instruction, licensing, and publishing.

Obviously a bad thing.

Byrne: “artists can’t really do a homegrown version of the on-demand streaming model.” Actually, they can and are actually doing that right now as we speak. Rabbit Rabbit and Deadmau5 are just two examples. I think it’s the future of all music. Bam! I just gave you the next big business plan in music. That’s how wolves… musicians… whatever… will make money as music streams like tap water. Each one of us will have our own branded “channel” where we directly engage and monetize fan relationships. This is a practical, logical way artistic control can be preserved in the transition from copyright exploitation to direct fan patronage. But it’s much more fun to say the sky is falling!

Oh, another understatement of the decade: “There has been a flowering of creativity and possibility somewhat thanks to the web.”

That’s like saying, “There was a great deal of reading and writing somewhat thanks to the printing press.”

Byrne is missing the point that the web is us. I’m all about respecting my elders but I’m not sure we should be taking cues for the future of music from a 61-year old who stands like a pale, naive foreigner amongst the digital natives.

“5. Streaming services are like broadcast radio, which music folks worried about at first, but eventually decided that it actually helped promote musicians work —- so some fees were waived.”

When broadcast radio came along, it threatened and co-opted labels. RCA bought Victor in 1929. The labels came fighting back, and a decade later we had BMI opening to lure artists away from labels and onto radio-owned properties. The standoff was settled by the government and that’s why we have this ridiculous entitlement system that was always broken and is now crumbling.

Eventually labels used payola to buy out radio and control the music marketplace and were able to get a final leg up on on radio, but not before they dumped a huge portion of their profits into independent promoters who greased the palms of broadcast programmers.

Today, corporate ownership of media and record companies is so consolidated, most negotiations are done behind closed doors with no input from musicians whatsoever.

This is the industry Byrne is defending in his piece.

Suggestion #1: “What if there was no free on-demand streaming (unless the artist is directly controlling that access through their own site or as a publicity endeavor).”

Byrne answered his own question, he just put parenthesis around the answer for some reason?

If you were being serious, then we have a unicorn to sell you. There is no world in which free on-demand streaming of music does not exist. Or rather, there is, and it’s a scary totalitarian dystopia where we’re likely to have bigger problems that stimulating musical productivity and creativity.

Suggestion #2: “Artists should get 50% of the income streaming sites now pay to labels”

Ha ha ha. We have a herd of unicorns to sell you.

Why does a post demonizing the music tech industry pose a solution that points out the real exploiters, the big three labels? Music rights corporations and industry organizations are clearly responsible for low musician wages, not tech companies.

Suggestion #3: “The artist should have approval whether his or her work can be used.”

Again, this is a label problem, not a tech company problem. Independent artists have total control to pick and choose each individual distributor. This is widely known… most musicians are independent. Welcome to the future of the music business: independence. It can be scary for people used to mailbox money, but we like it.

The only way to have total approval over whether your work is used is to not make it. Music is free. One way to create value around it is by controlling access through copyright law. But don’t confuse music with copyright.

Suggestion #4: “Transparent accounting and data sharing.”

Again, the labels are obfuscating. The tech companies are trending more transparent.

Is this whole thing just a Machiavellian scheme by labels to transfer their unethical history of corruption and exploitation onto a tech industry that wants to turn consumers into creators?

What is Byrne thinking? If the musicians that look up to him follow his lead, they’ll be more broke and confused than they were before they started blaming their own fans for destroying their music careers by sharing their songs out of pure love for the music.

Back to reality, folks!

photo credits: wolf by Arran ET; microphone by Paul Waite