“We are Ben Folds Five… When we started in Chapel Hill, NC in 1994 it was the heyday of grunge music. It was all guitars and no harmonies. Many said we didn’t know what we were doing. They were right. And in 2012, we still don’t. But we’re not alone now. Because in 2012, nobody knows what they’re doing. Except for Steve Jobs and Amanda Palmer.”

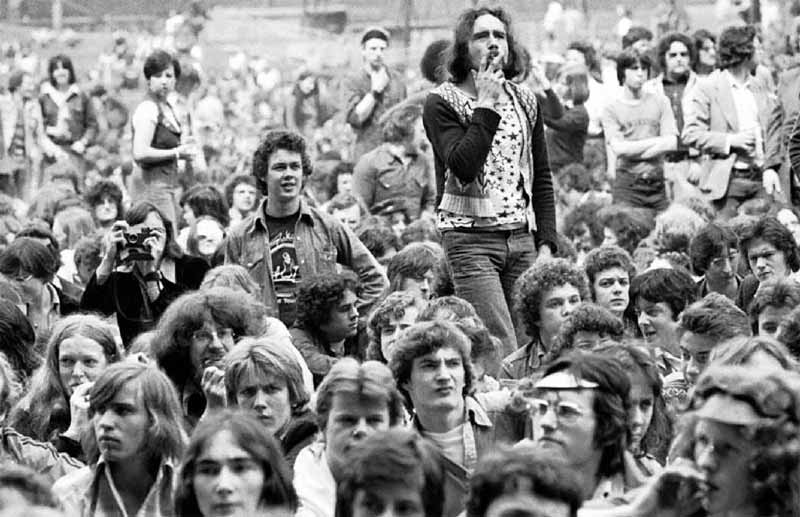

This is how Ben Folds Five opened their crowdfunding campaign video on Pledge Music.

Besides being incredibly funny to anyone who follows musician crowdfunding, it’s also illuminating. Crowdfunding for musicians — particularly those who have had success releasing albums in the “traditional” way — is often thought of as an “experiment”.

But what’s really more experimental: taking a loan from a record label where 9 out of 10 artists fail to turn a profit, or asking 100 or 1,000 or 10,000 or 100,000 of your biggest fans to finance the record with hardly any risk?

Even though Kickstarter raises more money for artists than the National Endowment for the Arts, crowdfunding is still an experiment?

Crowdfunding is no longer an experiment. It’s a proven formula. We’re still figuring out some of the details, but the theory is correct: fans want to support artists directly in exchange for exclusive access to the band and their creative output. If anything, it’s this musician perception of crowdfunding as “experiment” that’s slowing adoption — the fans are screaming at the top of their lungs asking for it like a back catalog request at a live show.

Musicians: the future is bright and under your control. Put on your shades and deal with it.

Of course, musicians themselves aren’t solely responsible for failing to adapt. The market itself has been slow to respond to the specific needs that surround crowdfunding an album.

There are relatively few companies that understand crowdfunding is going to be the dominant way albums will be made in the future. Certainly, you have the meteoric rise of Kickstarter and Indiegogo, but they have broader missions to change the dynamic of funding creativity in general.

There are only two companies right now that are seriously and directly competing for album-specific crowdfunding. They are Sellaband and Pledge Music. It’s unfortunate that their potential is to some degree being drowned out by the juggernauts of crowdfunding (Kickstarter and Indiegogo) because what musicians truly need is a crowdfunding platform created just for them.

There certainly aren’t only two companies competing for a share of the direct-to-fan artist revenue stream. Topspin, Bandcamp, Soundcloud, Reverbnation, Bandzoogle… the list goes on. The definition of “crowdfunding” could be made broad enough to include them. Here, I’m talking specifically about platforms that actually have people on staff to work with artists and their managers to produce album-specific financing campaigns.

I’m going to focus on Pledge Music because they share many basic features with Sellaband, but also have several major differentiators that I consider genius. Sellaband is the more established of the two platforms and I’m not trying to diss them, I’m just really excited about the potential behind Pledge Music’s particular approach.

Pledge Music is a managed music crowdfunding and retail marketing platform. The “managed” part? Pledge Music staff will actually set up and run your crowdfunding campaign, so it’s “white glove” service for musicians and their managers. They’re experts that will consult with your management and coordinate all efforts to minimize risk and ensure your fans are engaged and get exactly what they pay for. They’ve run the “experiment” of album crowdfunding enough to have established solid best practices for success, and have built the tools to facilitate that success.

You’ll pay a standard and reasonable 15% cut that includes all payment processing fees. With respect to its crowdfunding component, it’s analogous to what you know and love about Kickstarter or Indiegogo except for a few truly genius moves:

- Crowdfunding campaigns don’t end until the album is funded.

- The dollar (or euro) amount being raised is hidden from public. They only see what percentage of the album is funded so far.

- 99% of musicians on the platform opt to give a small portion of the funds raised to the charity of their choice.

- Musicians are encouraged to market to their fans through the platform with exclusive content as part of the value offering.

- When the crowdfunding campaign ends, a pre-sale window begins.

That last move is critical. When you think about it, there’s a blurry line between crowdfunding and a pre-sale. Most of the difference seems to be whether or not you have financing on the outset. So it makes perfect sense to start a pre-sale immediately after receiving financing. It’s one of those “why didin’t I think of that” strokes of genius that I see as the beating heart of Pledge Music’s common sense approach.

It’s the kind of sense that makes dollars. According to Pledge Music CEO Benji Rogers, my band left $1,661 on the table with when we recently raised $4,356 on Kickstarter.

That’s because Rogers has research showing 37% of the money raised by Pledge Music album campaigns comes in after the crowdfunding period ended. Ouch. That could have gone a long way.

See, on Kickstarter or Indiegogo, you build tons of buzz in the closing moments of your campaign to push toward and beyond your goal. Our goal was $3,666, which we hit about ten days before our campaign ended. We were able to push another $700 past that by pulling out all the promotional stops.

A few weeks later, we put the album up for pre-sale. We figured we wouldn’t get much interest because most of the fans that wanted it already got it through Kickstarter. But every day our inbox would pop up with new Bandcamp messages saying someone had pre-ordered the album. We saw the names and realized these weren’t old fans, these were new fans we’d attracted while doing all the crowdfunding promotion.

The secret to Kickstarter and Indiegogo is that they capitalize on one simple fact: true fans want more. They want the full brunt of your creative force. That’s why they’re patronizing your work. They want your creativity maximized, they want to have a hand in exposing others to what they love about your work. They don’t just want your music, they want your original lyric sheets, the shirt you wore on tour, and the bucket you puked in when you got off stage. Exclusivity is the new scarcity now that access to music is ubiquitous.

The average fan on Kickstarter contributed $39 to our campaign, as opposed to $5 for our pay-what-you-want pre-order on Bandcamp. If we turn out to have at least 42 people pre-order our album, as we’re on track to do, that actually works out to $1,661 we theoretically left on the table, because those people would have potentially purchased a reward package at a higher dollar amount had they taken part in the crowdfunding campaign.

There’s another, less obvious but very important reason to go with Pledge Music, and this applies to both small acts like mine, and the more widely known acts that seem to be Pledge’s bread and butter. It has to do with a very smart decision they made: The amount of money you’re trying to raise is never displayed in dollar amount. Users see what percentage of the goal was reached so far.

There’s this sort of inherent fear in setting your Kickstarter goal because the penalty of not reaching it is total failure. Since you also have to be 100% transparent on the amount, you’re compelled to set as low a number as you can get away with so your fan’s don’t think you’re overreaching. For example, we set our goal lower than we wanted to be safe and ended up unable to afford to hire a PR agent as we had originally planned. And there were still cost overruns in many of the rewards, some of which we’d planned for, some of which we hadn’t. On a larger scale this could have been disaster and is a fairly common complaint with Kickstarter. (Indiegogo is even more prone to this, because it rewards projects that fail to reach their goal, but takes a higher cut.)

Not only does Pledge Music have the expertise to help you avoid these problems, but their attitude is much more conducive to success: “Set the budget you need to do what you need to do, and you will get there eventually, just keep at it”. On Pledge, our band would have set our original budgeted goal of $6,000. We cut it down to $3,666 because that was our educated guess on how much we could realistically raise in 60 days, and we weren’t too far off. But it felt like the final round in the Price is Right.

Would it have taken longer than 60 days? Yes. Was there something about the deadline and the consequences that drove us and our fans to reach our goal? Yes. Obviously, it’s a big reason Kickstarter chooses to take its approach.

But here’s what it really boils down to: Behind every successful album on any platform — be it digital crowdfunding or just selling CDs out of the back of a car — is a successful manager. Kickstarter works because its platform that has features that enable the average artist to self-manage, whereas Pledge Music is built more as a tool that their campaign managers, along with the artist’s management, can use to engage the fans of the artist they represent.

You can read the case study on how our crowdfunding campaign succeeded, but basically, it was proper management and passionate promotion. I’m sure Pledge Music’s campaign managers can corroborate the amount of time and effort it takes to keep fans engaged is not to be underestimated. If I were scaling the crowdfunding campaign into five or six figures like most artists on Pledge Music, outsourcing management would quickly become mandatory.

The big lesson we’ve learned from watching projects fail on Kickstarter is that over-promising and under-delivering is a major risk. I’m reminded of many stories of indie bands that unexpectedly sold out of records or CDs and didn’t have the liquidity or production resources to keep the supply of recordings moving to fans. This is just a 21st century version of that problem.

So how to we convince musicians to embrace crowdfunding as the status quo for making albums? Education is a big part of it. With this blog and my online course, I’ve been doing everything I can to spread the word.

Ultimately, musicians will have to run the “experiment” themselves to see that it’s the most equitable financing solution for both musician and fan, potentially more lucrative than any record real if managed correctly, and much more rewarding from a basic human and artistic standpoint.

It will take companies like Pledge Music to convince musicians and their managers that crowdfunding is where music is headed. They’re going to need to better differentiate themselves from the Kickstarters and Indiegogos that dominate the market, while offering a user experience that is engaging for both fans and musicians. These are the areas that Pledge Music is weakest in. It’s not really standing out from the crowd in a marketing sense, and much of that has to do with a user experience that fails to be as innovating as the ideas behind it. Competing with Kickstarter is no small task, but I think Pledge Music has the potential to carve its own lucrative niche in the direct-to-fan artist revenue stream with the right leadership.

There is a simple principle at work behind the thousands of musicians successfully crowdfunding their own album releases on

There is a simple principle at work behind the thousands of musicians successfully crowdfunding their own album releases on