Last night, veteran musician David Bazan, known for being the man behind the seminal indie/emo group Pedro the Lion, played for a few dozen people in someone’s living room in Lubbock, TX.

Bazan spent almost half the year playing exclusively for people in living rooms. It’s not like he had to — his music career is quite accomplished. Tickets for his November/December tour of real venues are going fast, in part because he’s embracing another recent trend of playing classic albums in their entirety — in this case, honoring the 10th anniversary of Pedro the Lion’s finest concept album, Control.

Bazan clearly is right at home in yours:

Certainly, not every musician has the kind of intimate, almost humble delivery that makes Bazan’s solo performances a perfect fit for living rooms across America. But he is actually part of a long tradition that dates back to the origins of much louder, more aggressive music than his — punk and indie rock in the 70s and 80s.

Last year, NPR ran a blog post about the re-emerging popularity of living room shows, pointing out the convergence of digital event planning tools like Eventful with the new economic realities for musicians in a world of free or near-free access to recorded music.

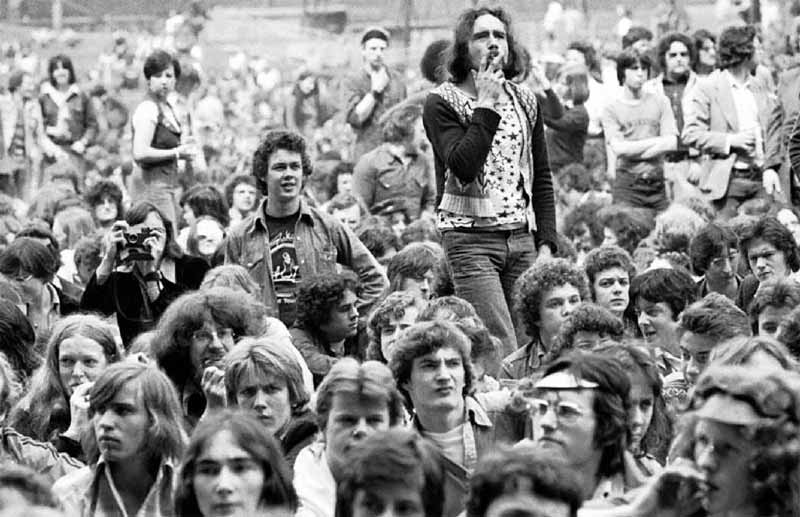

Most of today’s unsigned, independent bands that have toured the country with no booking agent and no management have played their share of living rooms. I know I have. But these living rooms are not often the kind of urbane, sitting-down affairs you see Bazan playing for 30-somethings. Rather, the hybrid living room/venue is rooted in “punk houses” where a bunch of high school and college-age music fans get together to hang out, party and host local and touring bands. I can honestly say from personal experience these house shows are some of the most fun and inspiring shows I’ve ever played. Our fans have crowdsurfed into ceiling fans more than once (pictured here). But the reason these shows are so memorable has just as much to do with the performance as it does with the camaraderie of being able to meet and entertain people in their homes.

Most of today’s unsigned, independent bands that have toured the country with no booking agent and no management have played their share of living rooms. I know I have. But these living rooms are not often the kind of urbane, sitting-down affairs you see Bazan playing for 30-somethings. Rather, the hybrid living room/venue is rooted in “punk houses” where a bunch of high school and college-age music fans get together to hang out, party and host local and touring bands. I can honestly say from personal experience these house shows are some of the most fun and inspiring shows I’ve ever played. Our fans have crowdsurfed into ceiling fans more than once (pictured here). But the reason these shows are so memorable has just as much to do with the performance as it does with the camaraderie of being able to meet and entertain people in their homes.

The real convergence spurring the living room tour revival can be explained by a concept I often use describe the music economy in an era of free music. The record business is no longer about selling content, it’s about selling context.

What I mean by that is, we never really paid for music, we paid for access to it. Now that access is relatively free, we’re paying for the experience of listening to it in a particular context. Besides a heartfelt need to compensate the artist (a sentiment that record labels destroyed through exploitation), pretty much the only reason people pay for music anymore is to have the convenience of accessing it in whatever context they’d like. There are few technological hurdles left in making music freely available this way, but corporate interests in the content industry continue to do everything in their power to prevent us from moving forward culturally. These corporations aren’t protecting the welfare of artists, they’re protecting their own bottom line.

As far as context goes, you can’t beat a live performance. Remember, before the phonograph was invented just over 100 years ago, the entire music industry revolved around live performance. Playing a piece live was the only way to summon music for listening, whether it was a world-renowned opera singer in an ornate hall or a family gathered around the piano in — you guessed it — their living room. With the record, suddenly we could experience music in any context we wanted… provided we paid the price.

But music is going back to the living room, and it’s headed there from two different directions. From the bottom up, more listeners are becoming amateur musicians. When they venture out to perform, they enter a network of home venues ranging from punk squats to the kind of well-kept living rooms Bazan has toured so successfully. Bazan doesn’t come from the bottom up, but nor is it at all accurate to say his career took a dive, requiring him to play living rooms. Rather, Bazan and more professional musicians like him are evolving their touring strategy to embrace modern music listening and consumption habits. He’s essentially an early adopter of a new model for professional music tours, where the idea of crowd sourcing meets a post-recording music industry in which context is the new commodity.

The truth is there’s not a whole lot of difference between the crusty punk squats and their tidier counterparts, dwelled in by young professionals — except, that is, for the money involved. At $20 a head, Bazan is charging a fairly comparable amount to a cover charge at a real venue. But consider that there are no other costs to cover besides food, transportation and lodging (some of which the hosts even provide). The venue gets no cut. The fans don’t have to pay for drinks, and have more money to spend on merch. And Bazan is almost guaranteed to make a killing selling merch because his audiences have a much higher concentration of total fanatics. That he sells out the vast majority of his appearances is a testament to this (although admittedly living rooms fill up pretty quick).

Now, the back-of-the-napkin calculation I come up with is that they’re netting in the low four figures at a sold-out show. A show at a “real venue” might be more lucrative for Bazan, but by what degree? And as a musician, I can tell you there is a certain psychological value in playing for a room full of fanatics instead of the somewhat random lottery of attendees at a “real” venue, not to mention all the business baggage that comes with dealing with promoters.

Bazan has clearly made a decision that these living room shows are the shows he wants to play even if it means taking a slight pay cut. Real musicians make music to celebrate its true meaning and power to move us emotionally, physically and spiritually, and unite us socially. We don’t make music to make money. Most of us simply want a lifestyle in which we can make our music, connect with our fans, and have them support us modestly. As direct musician-to-fan connections become the currency of the music industry, don’t be surprised if more well-known musicians start showing up in your living room.

Do you think today’s living room tours are more of the same, or is there something more there?