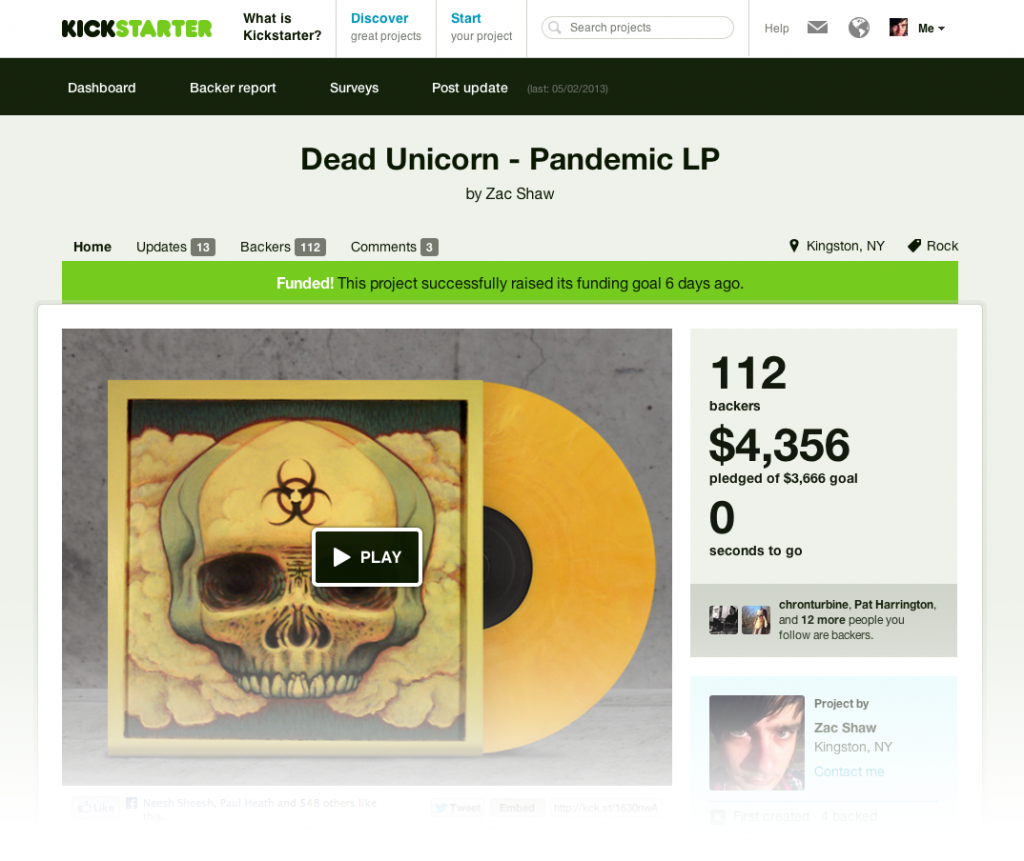

My band just raised $4,356 from 112 people in 60 days on Kickstarter to release our new album Pandemic.

I’ve been espousing the virtues of crowd funding for a while now, so I’m really glad we didn’t blow our goal of $3,666. Instead, we went $690 over our goal.

There were a few strategy/marketing moves that really worked, and a few unexpected but important issues that arose during the process. I’d like to share them here with my fellow musicians.

This isn’t about how to make a great video or a great campaign — I’m assuming your campaign is already totally awesome and your album rules. I’m here to give you the war stories so you don’t repeat the same mistakes and make real money with these Kickstarter best practices for crowd funding an album.

Why We Picked Kickstarter

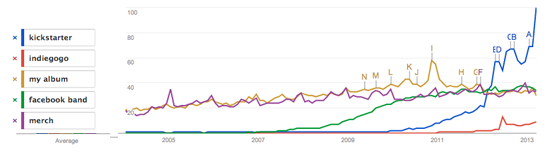

The first big choice is Kickstarter vs. Indiegogo vs. Pledge Music vs. Sellaband vs. Patronism. The last three were either overkill or still in beta. For most bands, the choice is going to be between Kickstarter and Indiegogo.

Kickstarter is the most established, fully-featured and polished of all the platforms. The only reason to consider Indiegogo is because unlike Kickstarter, you keep whatever money you raise even if you don’t reach your goal. You will pay a 9% fee instead of a 5% fee for this honor. When we weren’t 100% confident in our goal, we lowered it until we were. Indiegogo is perfectly fine (and charges the same 5% fee if you reach your goal), but we went with the established player. Remember, many of your backers will be funding their first project and will have to sign up with Kickstarter, so it pays to go with a trusted name.

Why We Set 60 Days to Achieve our Goal Instead of 30 as Kickstarter Recommends

I’m not going to dispute Kickstarter’s assertion that 30 days is the optimum length of a campaign — I’m sure their statistics clearly show it. But for us, 60 days was the right length. I think that for bands just getting their footing with marketing and sales, it’s better to have a longer window to utilize — think of it as a challenge to keep your audience’s engagement for a continuous two months. It’s hard to do, you will make mistakes, there will be lulls… but it’s a fantastic learning experience. If you’re not in any particular rush, more time will allow you to draw in more people from outside your fan base.

Delays to Watch Out for at the Beginning

Don’t expect to have your campaign up and running the day you decide to launch it… or, for that matter, anytime that week. Unless you’ve done a campaign before, you’re going to wait 2-ish weeks for Amazon Payments and your bank to work things out to where you can accept payments. You’ll need to provide tax info — oh yeah, you’re getting taxed on this income. You really ought to have an LLC and a business checking account, but you can squeak through DBA yourself with your personal account.

You may also be delayed if any of your campaign rewards (or any other piece of data) triggers Kickstarter’s moderators to flag your submission for violating the terms of service. That’s not limited to penises in the promo video and human blood as a $100 incentive. Our campaign was stalled because our top backer package offered free admission for life to any of our band’s gigs. Apparently, lifetime rewards are not allowed. There are dozens of “small print” rules like this. For us, it was an easy fix, but it’s important to be aware your launch can be delayed a couple days if it’s not up to spec.

Remember Shipping, Taxes, Fees and Declines when Budgeting

Setting your goal is all about figuring out how much money you are 100% confident you can raise, and then creating a budget to produce the album that matches that amount. When you do this, don’t neglect to factor in additional expenses that will have a significant impact on the money that’s left over to produce the record.

- Shipping – Shipping gets expensive quickly and is highly variable based on where the recipients live. You’ve really got to budget for shipping, and for that you have to guess how many of each package you’re likely to ship. Take your guesstimated total and round it up to be safe.

- Taxes – If your band has an LLC or a partnership, your company will be liable for the taxes. Otherwise, the person who handles the money will be on the hook. Like shipping, taxes are difficult for the average citizen to estimate, but you should be building in some room for cost overruns in your budget, and setting aside some money for taxes alongside.

- Fees – Kickstarter will take 5% of total funds raised, and Amazon will take ~3% for processing the payments (less or more depending on how much you raised). This quickly adds up to hundreds and even thousands of dollars in fees — you will wish you worked at Kickstarter when you see what they take out. Factor the fees into the budget!

- Declines – Backers’ cards are charged when the campaign ends. Depending on how broke your fans are, you may get a number of declined credit cards. Kickstarter tries to get the cash by sending alerts to the backer every day for seven days after the campaign. Then they give up, and the money is gone. Everyone’s going to have one or two declines, but some may have more. You’ve got a real problem when someone backs you to the tune of hundreds or thousands, and then their card declines, but there’s nothing you can do about that except try to build a relationship with that backer outside Kickstarter before the campaign ends (which is a good idea anyway).

In our case, all of the above added up to roughly 1/4 of our total production budget, so pay very close attention to fees and charges that may not be apparent at the outset.

By the way, we were worried about how long it would take to get paid after the campaign ended because we saw some people saying it took them up to two weeks. It took two business days for the cash to hit the Amazon account, and another day to transfer to our bank account.

The Hustle

A great video, a bunch of great packages, a great album… these are all… great. But they are nothing without the hustle.

Put briefly, we made a list of around 300 people we thought would back us at some level. We also had our 600+ Facebook fans and 300+ Twitter fans as a captive audience, and we hit them up every day. But as the deadline grew closer, we ran our 300-person list like we were doing a fundraising run against terminal illnesses.

Preaching to the choir is not everything — you absolutely have to be drawing in people from outside your fan base. Around 30% of our backers were total strangers to us before the campaign. We constantly were meeting new people on Twitter and pitching the album, and that was good for a few hundred bucks. Ditto on reaching out to the Creative Commons folks, who gave us a spot on their curated Kickstarter page because we license all our music CC-BY-NC-SA.

So get out there, meet new people, and get them to back your dream.

While the business aids are a great mix of fun and functionality, the true asset Artist Growth has to offer is a partnership with

While the business aids are a great mix of fun and functionality, the true asset Artist Growth has to offer is a partnership with