I have enjoyed satellite radio for the last three and a half years. There’s nothing quite like genre-sorted, slightly random playlists of singles peppered with a few b-sides.

But here’s the truth: Sirius XM sucks.

You bet Top 40 radio is unlistenable! Who wants to listen to advertisements for music sandwiched between advertisements for products when there are so many other options?

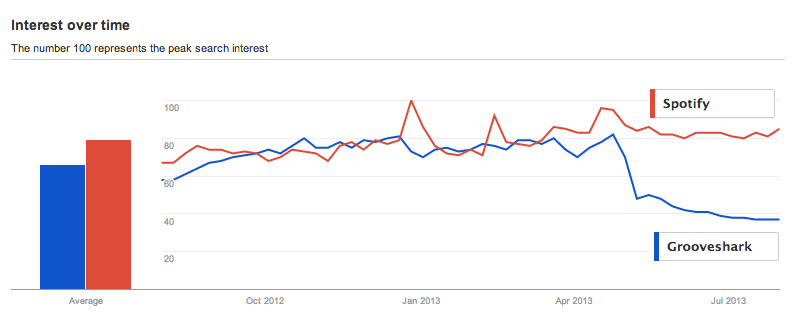

Pandora, iTunes, Spotify, Grooveshark, Turntable.fm… they’re all great on a desktop, workable on mobile, but get most into a car and you’re a slave to cell signal strength.

It’s crazy that a world of digital music still can’t compete with satellite radio for convenience in the car. And it’s all because they followed the business model of the 8-track cassette — build the damn thing directly into the dashboard of every American-made car.

Sirius XM has a market monopoly on delivering music via satellite. I’ll admit it, I hated them even before using the service, and I ended up a customer anyway.

In 2008, the FCC approved the merger of Sirius Satellite Radio and XM Satellite Radio, basically saying it was OK to create a satellite radio monopoly because otherwise the companies would go out of business due to competition from digital.

The merger was a profitable move for both companies. Without the government’s blessing on its monopoly, satellite radio might have gone the way of the 8-track. But the industry elite had deemed satellite radio too big to fail.

The merger was not good for artists or fans, but who cares about them, right?

No, this blog post is not about the obvious ethical bankruptcy of the FCC or of large media conglomerates like Sirius XM. It’s about my personal experience with their predatory billing practices, poor promotional ploys and abysmal customer service that led me to cancel my subscription today.

I ended up with satellite radio as most people do — with a free 6 month trial in a new car. When the six months was up, I was offered a great introductory deal. I forget exactly what the rate was, but it was far less than the $18.99/month default payment plan ($227.88 when billed monthly for a year). I made sure that I was purchasing a single year of service, and made sure Sirius XM knew they did not have my authorization to charge my card after my year was up.

$227.88 per year is waaaaaaay too much for satellite radio. And this is the low end of the cost — if you don’t own the hardware or want to access your Sirius XM online, it’s going to cost you extra. If the FCC’s intent was to ignore the issues of customer price fixing and price gouging in order to maintain satellite radio’s profitability, they did a great job.

But nobody pays $227.88 for their first year of Sirius XM. They sign on for 30%, 40%, 50% off or more. And like any bait-and-switch introductory rate, the fine print says that unless you call to cancel your subscription, you will automatically be billed the full $18.99/month in perpetuity.

After my initial free six months and toward the end of my killer one-year deal, I started getting the expected renewal offers in the mail. There seemed to be a new one every two weeks — even before I could consider the 50% off, they were throwing 60% off at me. 70% off. Finally, I got an offer to get 6 months for $25. The regular price for 6 months of service is $113.94. I took it.

Only now, they wouldn’t accept my terms not to auto-bill my credit card. After much insisting, they finally told me that there was no way to have a subscription without it being automatically renewed and billed. I could pay by check, but the service would auto-renew and a new check would be due unless I called to cancel.

So, like your typical idiot consumer, I made a mental note to cancel my account right before the “six months for $25” deal expired, and I forgot. I spent a year paying the $18.99/month like a chump. Had I only taken 20 minutes out of my day to call Sirius XM and threaten to cancel my account, I could have been paying $4.17/mo. instead of $18.99/mo.

Folks, if you like Sirius XM radio and you’re not paying $4.17/mo., put that 20 minute cancellation call on your calendar right now. You can thank me later for saving you a few hundred bucks a year.

I’m not ashamed to admit I probably would have gone on paying $18.99/mo. like a chump had my debit card not fortuitously expired. This required Sirius XM to call be to update my billing information, and that’s when they began to really lose me.

The customer service nightmare began, as it often does, with an underpaid customer service representative in a foreign country where labor is cheaper.

I gave my updated payment information and then asked to have my subscription taken off of automated billing and renewal. I told them straight up that I wanted to stop auto-renewal because in the past I had received attractive offers to rejoin when I let my account lapse. Again, I was informed this was not possible. Even though satellite radio is a luxury, Sirius XM portrays its company as a utility when explaining why every subscriber is forced to auto-renew. And their policy is not to notify monthly subscribers before their subscription is auto-renewed. The policy glistens with slime any way you look at it.

“If I could not stop auto-renewal,” I told them, “I would like to cancel my account.” That’s when the barrage of offers started coming. 60% off, 70% off, all the way back down to six months for $25.

I insisted that unless there was a better offer, I would like to cancel my account and see if I can get a better offer after canceling.

The rep then asked if I would like to finish out my current plan. I said sure, seeing as there were only a few months left and assuming I had already been billed the annual fee. What I didn’t realize was that I was still being billed monthly, this monthly billing was part of a year-long block of billing time. So with a few confusing words, the rep convinced me of finishing out the year with Sirius XM (my “current plan”) and then having my service cancelled. I settled last month’s fee, agreed to pay out the remaining four months of my plan, and then my account would be cancelled.

It occurred to me that I had just accomplished what I was told was impossible — to continue to get Sirius XM service without my subscription being auto-renewed! Success!

Then I got a call on Friday that would be the beginning of the end.

You know it’s one of those calls when you get the awkward 2-second pause between saying “Hello” and hearing the rep saying his or her call script. When I heard the rep was from Sirius XM I couldn’t believe it. Here I had already cancelled my service, and they were calling me to renew. I didn’t mind that I had already received a couple of letters in the mail from Sirius XM offering me the $25 for 6 months deal. But calling me on the phone, direct telemarketing, was just over the top.

I told the rep that it wasn’t a good time and to call back later, but I had my mind made up. Finishing out my plan was not worth it if I was going to be harassed by customer service. I would answer their call and cancel.

They called once in the morning and once at night for four straight days. I admit, I didn’t pick up because I wanted to see how long they’d go for. Finally, this morning, I picked up and got yet another surprise.

Even though I had updated my billing information the previous month, Sirius XM was calling me to update my billing info because the card they had on file was expired. This despite taking and successfully processing new billing info last month. And what happened to the “plan” that I was finishing up? If I was being billed monthly, what the hell was the “plan” the last rep was referring to in any case?

At this point I couldn’t tell the difference between their mistakes and their scams. All I knew was that I wanted out. I updated my billing info (for the second time) and was transferred once again to the cancellation department.

I understand the game. When you call to cancel your service contract, you run the gauntlet of incredible deals meant to coerce you into doing anything but cancel. It starts with the magic question: “May I ask why you are canceling?” From there, your conversation branches off in one of two directions. Say you can’t afford it and they will offer you discounts until you can (at least for the next six months, after which you’ll be auto-renewed at the unaffordable rate). Say you have a problem and they’ll throw the same deals at you, and maybe add on a month or two of free service for your grievances.

I explained that my problem was that I found it unethical that Sirius XM was bait-and-switching its customers, auto-renewing subscriptions for premium fees after getting cards on file at introductory rates. I thought they were being predatory by not clearly disclosing that their business model was to sign you up for $4.17/mo. and then begin billing you $18.99/mo. six months later with no notification. I told the rep that I understand the need for promotional deals, but the sheer number of different proposals, and the universal nature of their deceit, had finally gotten to me. Finally, I told the rep that I knew Sirius XM didn’t care and probably wouldn’t listen to my concerns but maybe, just maybe, she could talk to her boss and relay my concern that Sirius XM’s predatory billing practices are unsustainable.

In most situations, there is nothing you can do to change a corporation other than to not patronize it. Luckily, I can do something more than just cancel my support for the satellite radio monopoly. This blog gives me the platform to let others know: Sirius XM needs to change its billing practices, because more customers each day are realizing they’re complicit in unethical business practices. We see the switch behind the bait. We see through the false empathy of the customer service training. We understand your business exists solely to make a profit and has long since parted with any intention of fostering the greater good of musicians and their fans.

We understand that Sirius XM fights against musicians to pay a lower royalty rate on the music they exploit. We understand that digital devices and connectivity would have killed the satellite radio business model already if not for the enormous (and potentially flagging) support Sirius XM buys from automakers.

Today I cancelled my Sirius XM subscription. I will miss the occasional discovery of a new artist. I will miss the ability to turn on CNN to hear up-to-the-minute descriptions the latest thing to be blown up and/or engulfed in flames. I will miss it on long drives when I most need musical surprises to break up the monotony.

I won’t miss relinquishing control over the terms on which a company takes my money. I won’t miss the incessant attempts to bait-and-switch me back as a customer. I won’t miss feeling complicit in the exploitation of all the artists on the station, whom Sirius XM lobbies against paying. I won’t miss the customer service hold time, or the feeling of having my concerns ignored.

Today, and for as long as people Google “Sirius XM sucks”, this blog will be there to remind the Sirius XM corporation and its employees: The legitimate value of your service is being undermined by the exploitation of your customers and those who made the music that gives your service value. You will profit in the short term, but the business will be unsustainable in the long term. Tomorrow’s headlines are “Sirius XM Goes Way of 8-Track”.